Blog

Can governance reform restore confidence in UK Universities?

UK universities face intense scrutiny and financial strain. This blog examines how governance reform, anchored in the forthcoming revision of the CUC Higher Education Code of Governance, can strengthen assurance, clarify roles and rebuild confidence across a diverse sector.

Blog

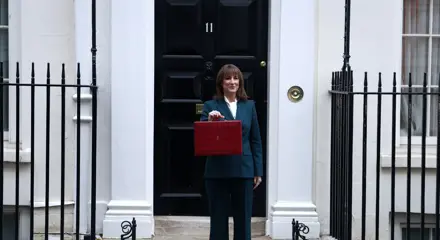

Budget 2025: Key considerations for governance professionals

Budget 2025 arrives at a moment of economic uncertainty and shifting expectations for public bodies and businesses alike. The Chancellor’s announcements will carry significant implications for governance, accountability and organisational resilience.

Blog

Comment: "Why becoming Chartered was the most important step in my career"

Ruairí Cosgrove FCG, President of CGIUKI, explains why becoming Chartered was the defining step in their career. From law and strategy to ethics and communication, the qualification opens doors to influential, purpose-driven roles across sectors.

Blog

Are the rules of governance different in media organisations?

Governance in media organisations faces intense pressures where trust, editorial independence and political influence collide. From the BBC’s recent turmoil to Fox News’s costly settlement, boards across the sector are under scrutiny as they navigate a landscape where governance principles come under the spotlight.

Blog

Comment: "Governance gatherings are pivotal to professional growth"

With governance under pressure from rapid change and rising risk, the CGI Scotland Conference 2025 offers a space for professionals to connect, collaborate and stay ahead. In this comment piece, Gary Gray FCG explores how convening across sectors strengthens resilience and why community is now central to governance excellence.

Blog

What the Captain Tom case teaches us about governance and trust

The Charity Commission’s inquiry into the Captain Tom Foundation exposed repeated misconduct and mismanagement by Hannah and Colin Ingram‑Moore. Its report cited failures in conflict management, oversight and intellectual property arrangements, offering stark lessons for boards on independence and transparency.

Blog

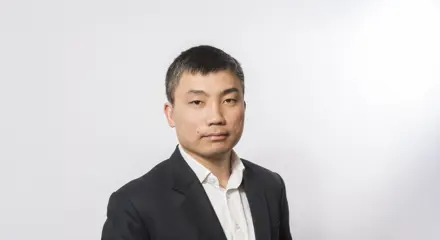

Comment: "Ethical leadership needs company secretaries who do more than manage process"

Peter Ho FCG urges company secretaries to step up as strategic partners in ethical leadership, helping boards move beyond process to build integrity, challenge blind spots, and prepare for complex governance challenges.

Blog

From the CEO: It is an immense privilege to begin my role as your new Chief Executive

I join at a moment of both challenge and opportunity for our profession. That is why our membership survey is so important. It gives us the evidence to shape strategy, measure impact, and decide what we should start, stop or strengthen.